This is a guest post by sports journalist Cecil Harris, who has covered major tennis events including the U.S. Open. He has written for the New York Times, the Associated Press, and USA Today. He is the author of several books, including “Different Strokes: Serena, Venus, and the Unfinished Black Tennis Revolution” and “Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis from Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to the Williams Sisters”.

In the 1950s, Althea Gibson became the first black player to win Grand Slam tennis titles. She won eleven in all—five in singles, five in doubles and one in mixed doubles.

Her triumphs occurred almost half a century before Venus and Serena Williams won Grand Slam tournaments and revolutionized their sport, and more than a decade before Arthur Ashe won his first major title.

But unlike Serena and Venus, who have become global sports superstars, and Ashe, a humanitarian whose name graces the world’s largest tennis venue—the 23,000-seat main court at the U.S. Open—Gibson remains largely unknown.

But unlike Serena and Venus, who have become global sports superstars, and Ashe, a humanitarian whose name graces the world’s largest tennis venue—the 23,000-seat main court at the U.S. Open—Gibson remains largely unknown.

Of course, the social diseases of racism and sexism have been factors in the historical obscuring of Gibson, a woman who integrated two sports. After her tennis career, she became the first black player on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour, where she competed from 1963–77.

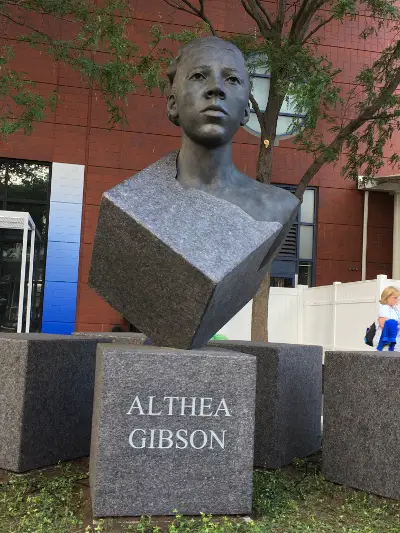

However, the tennis establishment also bears a large responsibility for Gibson not being better known. Until the unveiling at the 2019 U.S. Open of a bust of Gibson, America’s Grand Slam event had nothing significant named for her. It’s an especially galling oversight because Gibson grew up in New York City—less than 10 miles from the U.S. Open venue.

Even the sculpture is an inadequate tribute. Although it shows visitors what Gibson looked like, it does not tell them what she accomplished.

Gibson excelled when tennis was an amateur sport. She won her first Wimbledon title in 1957, defeating Darlene Hard, a part-time tennis player and full-time waitress. Queen Elizabeth presented Gibson with the golden championship plate. Gibson won the French Nationals in 1956 and consecutive Wimbledon and U.S. Nationals titles in 1957 and 1958, and was ranked world No. 1. Yet as a champion way ahead of her time, she barely made a dime.

Ashe, in contrast, became a star in professional tennis. He won the first U.S. Open in 1968. That year, CBS televised the tournament nationally for the first time. For millions of TV viewers who did not see Gibson, Ashe became known as the black tennis champion.

Handsome, well-mannered and well-spoken, Ashe projected an image that appealed to tennis fans and corporate sponsors alike. In addition to his success on the men’s tour, Ashe worked as the head tennis pro at the Doral Resort and Country Club in Miami. Gibson never received such an opportunity.

Gibson broke tennis’s color bar at the 1950 U.S. Nationals (precursor of the U.S. Open). When she conquered Wimbledon seven years later, tennis results were not readily available to the public.

“Althea called my mom to tell her she had just won Wimbledon—that’s how we found out,” said Gibson’s nephew, Roger Terry, who was seven at the time. “You didn’t have TV coverage of tennis then, so I remember waiting around for the phone to ring to find out how she did.”

Weeks after her Wimbledon triumph, Gibson became the first black woman to receive a ticker tape parade along New York City’s Canyon of Heroes. Yet it did not result in any significant endorsement deals. She still struggled financially.

In announcing her retirement from tennis in 1958, Gibson told a New York newspaper, “I have traveled to many countries, in Europe, in Asia, in Africa, in comfort. I have stayed in the best hotels and met many rich people. I am much richer in knowledge and experience. But I have no money.”

It’s a wonder that Gibson accomplished as much as she did in tennis with the deck so stacked against her.

For instance, in the 1950s, the U.S. Nationals were held in two different venues—singles at the West Side Tennis Club in New York and doubles at the Longwood Cricket Club in Boston. Players were invited to compete. From 1950–56, Gibson was not invited to the doubles tournament. That racially biased decision denied her the chance to win as many as 14 additional major titles.

Gibson was born on a cotton plantation in Silver, South Carolina, in 1927. Her family moved to Harlem, in New York City, when Gibson was three. She died in 2003 at age 76. Ashe was born in 1943 in segregated Richmond, Virginia. He died in 1992 at age 49. Both tennis legends faced racial discrimination. However, Ashe’s stance as an activist in the black struggle for civil rights and the global human rights movement afforded him much more favorable media attention than Gibson’s tennis-centric stance in the 1950s.

Ashe, erudite and tactful, had an ability to engage people in discussions about race relations in the U.S. and abroad without antagonizing them.

In 1973, Ashe took a highly publicized trip to South Africa to raise public consciousness about the everyday horrors faced by blacks under the country’s apartheid regime. He also partnered with entertainer Harry Belafonte to found the group Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid.

Gibson, meanwhile, shunned media attempts to label her “the Jackie Robinson of tennis.” A number of journalists, particularly black journalists, found her gruff and standoffish. That she was unwilling to speak out on behalf of the civil rights movement and steadfastly refused to regard her tennis victories as triumphs for her race kept the black media from embracing her. Russ Cowans of the Chicago Defender, an influential black newspaper, wrote, “Instead of presenting Althea with a trophy, the Queen [of England] would have done the field of sports a real service if she had given her a few words of advice on graciousness.”

In response, Gibson wrote in her 1958 autobiography, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody, “I feel strongly that I can do more good my way than I could by militant crusading. I want my success to speak for itself as an advertisement for my race.”

It’s not that Gibson’s viewpoint was blatantly wrong. But it alienated many who could have advocated for her after her playing career. As her employment opportunities diminished, her celebrity status faded.

Hence, when the U.S. Tennis Association named its new No. 1 court at the U.S. Open in 1997, it did not consider Gibson. The USTA looked instead to Ashe, a humanitarian who also played a mean game of tennis. Harry Mannion, then the USTA president, announced the naming of Arthur Ashe Stadium “because Arthur Ashe was the finest human being the sport has ever known.”

The tennis establishment could do much to spark interest in Gibson seventeen years after her death: Name an award after her, such as the U.S. Open women’s championship trophy, which currently has no name. Establish a charitable initiative or scholarship program in her honor. Presently, only the Volvo Car Open in Charleston, S.C., has a court named after Gibson.

That’s not enough. One court in South Carolina and one bust at the U.S. Open for such a trailblazing champion are too little and too late.