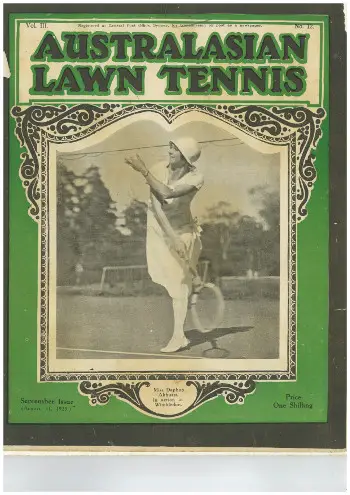

Women’s Tennis Blog is known as a go-to place for latest on-court style information, but we never really analysed the historic development of tennis apparel. The 1920s were arguably the decade when the most important of all changes were made to women’s tennis dresses. Sports historian Richard Naughton will tell us more about this revolutionary period, using excerpts from his recent book about the 1920s Australian player Daphne Akhurst, “The Woman behind the Trophy”.

In the 1920s, ladies’ tennis dresses went from ankle length with multiple petticoats to just below the knee and no petticoats at all. At the start of the decade the ladies also wore long-sleeved blouses, buttoned at their wrists. By 1930, sleeves were a thing of the past. Players were able to swing their arms about for all to see. Almost all these changes were courtesy of the remarkable Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen. She revolutionized women’s tennis fashion. Lenglen arrived at Wimbledon as a 19-year-old, the first post-war Wimbledon in 1919, wearing what was called “a shockingly skimpy ensemble”, that was borderline “indecent”, but she won the event and became the game’s first major star and “fashion icon”.

In the 1920s, ladies’ tennis dresses went from ankle length with multiple petticoats to just below the knee and no petticoats at all. At the start of the decade the ladies also wore long-sleeved blouses, buttoned at their wrists. By 1930, sleeves were a thing of the past. Players were able to swing their arms about for all to see. Almost all these changes were courtesy of the remarkable Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen. She revolutionized women’s tennis fashion. Lenglen arrived at Wimbledon as a 19-year-old, the first post-war Wimbledon in 1919, wearing what was called “a shockingly skimpy ensemble”, that was borderline “indecent”, but she won the event and became the game’s first major star and “fashion icon”.

Every year Lenglen played at Wimbledon from that time, she introduced new fashion innovations. It was Lenglen who introduced the coloured bandeau (the scarf which held her hair in place), and the colourful sweater to match. The dresses she wore became lighter and flimsier, as noted, the sleeves were discarded completely.

Daphne Akhurst was fascinated by Lenglen when she travelled overseas in 1925 and she wrote about her in the Sydney Sun, acknowledging the role played by the Frenchwoman in setting the style for other female players:

Suzanne Lenglen, not content with setting the style in tennis, seems to have decided to become also the leader of Wimbledon’s fashion. Her frocks are silk, short cut, and sleeveless, and the skirt is box pleated. But her colour scheme of bandeau, sweater and scarf to match are as unique as some of her shots. She never appears in the same colour two days running. Even while watching a match from the gallery, she has been known to run down to the gallery and change her dress. Once while playing in France, Suzanne suddenly left the court before her match and rushed to the dressing room. Mrs Utz saw her and asked the matter. “My dear”, she said, “I have just seen someone in the same colour bandeau as myself”. It is impossible because she is so fat. The same colour bandeau as mine – and oh, so fat! Voila!”

From this time, the view became that female players should strive for the “most comfortable attire possible” and the ladies’ tennis fashions during the twenties were said to be ideal for comfort and appearance. Most of the other female tennis players followed Lenglen’s trail. They wanted to jump and run freely as well! Generally, they wore rolled socks over their stockings to protect their feet, but Suzanne considered these ugly and refused to wear them. Daphne seems to have been attributed with popularising “rolled top” ankle length sport socks and introducing them into Australia. It became popular with good sturdy players and with the girl who merely “dressed tennis”. The rolled-up sock saved the silk stockings from unsightly spattering and could be obtained in different tones to match almost any shade of costume and stockings, with a pretty contrasting band at the top to match hat or bag!

One problem at the time was press photographers who made it their task to take “pictures” of lady players dressed in the new “provocative” outfits. When Daphne reported back in her newspaper columns, she told readers that the gentlemen took their photographs “while practically lying on the ground.”

Then, there were more “fashion” changes later in the decade. In 1927 Billie Tapscott of South Africa turned heads when, while practising on a back court at Wimbledon, she played without stockings – the first time a woman player had ever done so. Tapscott looked a little surprised and told alarmed officials that this was how they always played back home in South Africa. Tapscott was a fine player who reached the Wimbledon quarterfinals in 1929, but her fashion faux pas, was regarded as quite disgraceful for Wimbledon in the 1920s. It is remarkable considering the fuss the incident caused, that within four years or so, all lady players played without stockings!

The issue of “stockingless female athletes” became the subject of comment in newspaper articles of the time in Australia, and Daphne showed herself to be somewhat conservative on matters of this type.

The principal matter of alarm arose in 1929 when Helen Wills, the great American player, appeared in Paris at the French Championships with “the calves of her legs unclothed.” A fussy English writer, in search of a headline, was struck by the thought: “Will this happen at Wimbledon? Will Helen Wills dare to appear on the centre court without stockings to clothe her legs down to the ankle?”. Miss Wills, also known as “Miss Poker-Face” because of her businesslike style of play and lack of emotion on the court, had been approached for her view about the controversy. According to the story she looked sternly at the reporter and briskly told the man that anyone who found bare calves shocking must have a low mind.

Back in the 1920s, however, the Wimbledon committee was extremely serious on matters of this nature and it wasted little time laying down an ultimatum, which was, in effect, that in its view, the removal of stockings, was simply too shocking.

Another important fashion issue that took place at the end of the decade in terms of women’s fashion was the question whether it was permissible for female players to wear shorts. At one point the Sydney Sun included an article headed “Is the wearing of smart shorts by our tennis girls likely to disturb our code of public morals?”

This issue of playing in “shorts” was another matter where Daphne’s views, and those of fellow Australian players, seemed a little hesitant and perhaps “traditional”, in retrospect. She suggested at the time that shorts were “unnecessary and silly.” “I am against them”, Daphne remarked, “The present dress with a full skirt is suitable enough”. Her view was that apart from when they were worn on the beaches, shorts on women were “ugly”.

It is interesting to note that Daphne’s comments (in May 1931) were made shortly before her friend Lili de Alvarez made a form of shorts haute couture at Wimbledon. De Alvarez played at Wimbledon in 1931 in an experimental outfit designed by Elsa Schiaparelli consisting of a two-tiered, pagoda-type tunic with flared trousers. This “pantsuit” became internationally famous, and certainly didn’t fit into the category of “unnecessary”, “silly”, or “ugly”. What would Daphne’s view have been if she had known this when she made her comment?

There have been many significant changes in women’s tennis fashion since the 1920s – Gussie Moran’s lace underwear of the late 1940s; the body-fitting dresses of Tinling in the 1960s; the white bodysuit of Anne White at Wimbledon; Serena Williams’ black bodysuit; the current day dresses produced by sporting goods manufacturers for the stars – all interesting changes perhaps, but largely tinkering at the edges. It is still possible to argue that all the major changes took place in that single decade of the 1920s.

The book Daphne Akhurst – The Woman behind the Trophy is available through the slatterymedia.com website as well as e-book and Amazon sites.